Chief financial officers well-versed in regulatory matters may want to give their human resources colleagues a heads-up regarding the human capital disclosures they’ve been working on together for the past six quarters — specifically, the typical development formula that regulatory guidance follows over time:

Principles-based reporting requirements + Additional guidance and comments = Rules-based reporting requirements

If this well-worn pattern in the lifecycle of regulatory guidance and requirements holds, CFOs and chief human resources officers (CHROs) should expect the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to issue more definitive guidance on the human capital disclosures that publicly listed companies have been required to include in their annual reports since late 2020. Rather than waiting for this clarity to materialize, however, CFOs can take tangible actions — often in collaboration with their CHRO counterparts — to sharpen these disclosures in ways that will at least meet the yet-to-be-fully-clarified reporting thresholds envisioned by regulators as well as be responsive to the needs of stakeholders who are showing greater interest in the organization’s human capital programs.

In August 2020, the SEC issued a rule requiring companies to report on human capital metrics. The rule became effective in November 2020. Specifically, the amendment to SEC Regulation S-K Item 101(c)(1)(xiii) requires human capital disclosures “to the extent such disclosure is material to an understanding of the registrant’s business taken as a whole.” This investor-driven requirement is designed to modernize financial reporting by adding an element that is being scrutinized increasingly by investors, customers and even employees.

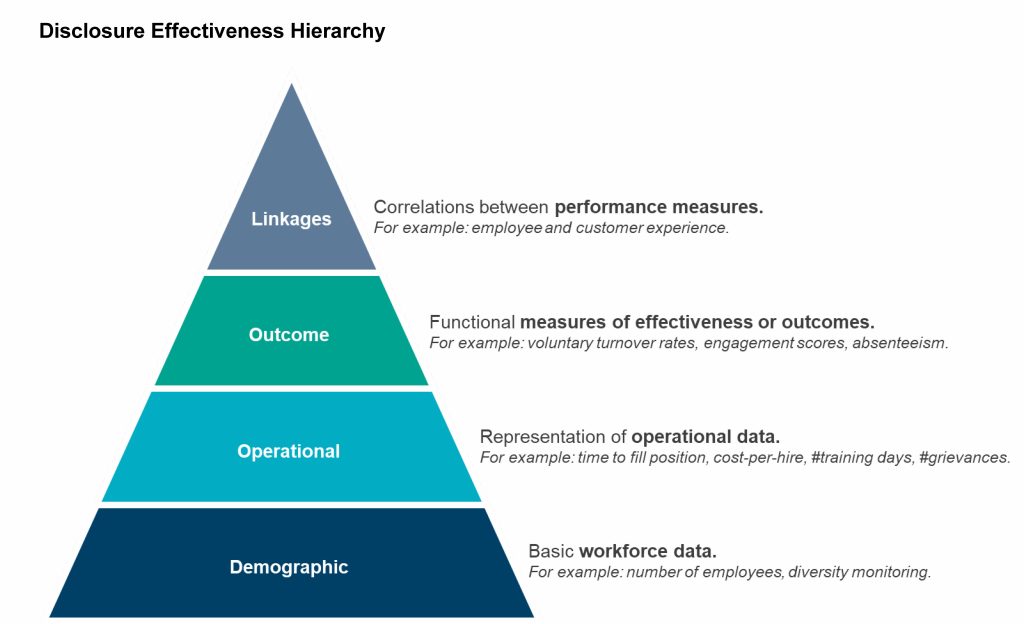

The language of the new principle-based rule grants companies latitude to shape the content and format of their human capital reporting. This explains, in part, why the vast majority of human capital disclosures thus far consist of largely aspirational statements about diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI); the employee experience; living wage; and other talent and human capital management areas. This would fall in the “basic data” category shown in the accompanying “Disclosure Effectiveness Hierarchy” graphic.

A smaller group of public companies have provided more detailed human capital information, supported by numbers and, in some instances, functional measures on effectiveness or outcomes (e.g., employee engagement assessment scores and investments in training and development). An even smaller portion of human capital reports provides these measures while establishing correlations between human capital and the bottom line via quantifications such as the return on investment for talent (ROIT). These matters are reflected in the accompanying graphic as higher tiers of reporting maturity.

While aspirational statements may be fine for now, SEC history tells us they may not be for long. Experienced CFOs who have been around the block a few times know this all too well.

Organizations should expect more specific requirements to come soon from the commission, either through the ongoing comment process on filings or through additional guidance. If they are to elevate their human capital reporting maturity, the organization’s board and executive team will need to keep in mind the following points:

- Human capital reporting requires the CFO’s involvement. Human capital disclosures established a new class of information for SEC reporting. A prudent approach starts with identifying measurements and outcomes (the bigger-picture framework), followed by metrics that support the framework. As with financial reporting, supply chain and other data, all of the content in this report must be factual and verifiable.

- For most CFOs, this represents a new reporting dynamic. While the CFO purveys, and vouches for, the human capital information contained in annual reports, CHROs and their groups are responsible for providing the data used to create the necessary metrics and reports. CHROs generally have limited experience quantifying and validating measures presented to regulators and shareholders. This dynamic necessitates effective collaboration between the CFO and CHRO. Again, there is a discipline underpinning the public reporting that CFOs understand all too well.

- The human capital reporting requirement reflects the growing demand for finance—and finance-adjacent — insights. In recent years, the CFO and finance function have been responding to rising demands for financial analyses from an expanding group of internal customers. In addition to closing the books accurately and on time, CFOs and finance teams have become their company’s go-to insights providers. While the bulk of data used in human capital reporting does not reside in corporate finance systems, CFOs nonetheless are expected to ensure the accuracy, efficacy and relevance of this information, including the effectiveness of the underlying disclosure controls and procedures. After all, the CFO signs the quarterly Section 302 certification along with the CEO. Here, the finance organization’s experience and acumen in data-driven reporting are invaluable.

To prepare for what may become more specific rules-based requirements for human capital reporting, smart CFOs will recognize the opportunity to contribute value to the process and lead the way in undertaking a number of important steps. First, finance leaders should consult with their C-suite peers to ensure that any aspirational statements within the human capital disclosures properly and accurately frame the company’s vision and objectives. A montage of dreams is not suitable for public reporting. Next, the CFO should work closely with the CHRO to develop ways to quantify the links between human capital investments and performance and/or profitability. Deploying calculations such as ROIT will elevate the maturity of the company’s human capital disclosures while also helping to forge a stronger finance-HR partnership.

Finally, CFOs and CHROs should compare their human capital disclosures to those from other organizations that contain the strongest links between human capital strategies and business outcomes. These exemplars in investor relations and reporting tend to reside in industries where human capital matters have an outsized impact on performance. In healthcare providers, for example, contract labor is extraordinarily expensive — as much as four times the cost of a regular full-time employee. Since healthcare providers do not have the option of short-staffing areas such as emergency rooms and surgical facilities, the cost difference between taking 30 days and 180 days to recruit and fill positions is significant.

The magnitude of these financial impacts often results in more rigorous human capital metrics and disclosures. Similar calculations and correlations can be applied to diversity and inclusion, employee experience, pay equity, and other human capital programs — not to mention broader sustainability initiatives. These efforts will help meet investor requests, or demands, to better understand the business while sustaining compliance with disclosure requirements that may soon afford CFOs and HR leaders less reporting latitude.

Referring back to the formula cited earlier, I mentioned “additional guidance and comments.” When the SEC comes down from the mountain with additional clarity as to its expectations in this area, CFOs should caution their CHRO counterparts that the SEC staff will likely include more specific questions and requests relating to human capital disclosures in comment letters to the company in response to its filings. Typically, the staff’s intent is to parlay the commission’s guidance into more rigorous and consistent reporting. Comment letters and the company’s response are part of the public record, and can therefore be part of the company’s research regarding trends. Diligence in addressing the above suggestions should reduce the duration of last-minute efforts to address these comments and the related impact on company disclosures.

This article originally appeared on Forbes CFO Network.